In the Eye of the Storm, Literally

- Jim Clash

- 5 days ago

- 3 min read

Intermittent lightning flashes near our U.S. Air Force C-130 aircraft. The odd smell of ozone from the outside electric interaction with air in the atmosphere is noticeable in the plane.

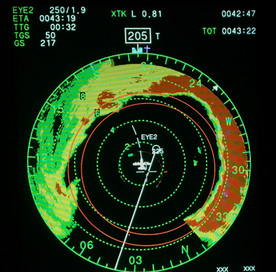

But the wind is eerily calm now, here in the Eye, a far cry from just minutes ago when we passed through the final part of the menacing Eye-wall of Hurricane Dorian. Stars are visible overhead out of the cockpit window. When we entered the storm earlier, it was classified Category 4, with winds of over 150 mph. Now it is teetering on Category 5. We just saw 167 mph on the plane radar gauge.

I try to enjoy the calmness and the beauty. The stacked white cloud formation surrounding the Eye, an oval of sorts, resembles an immense structure from the center of a football field. It’s known by storm chasers as “The Stadium Effect.” The serenity in the Eye makes it hard to imagine the destructive violence in the seemingly peaceful clouds we had just traversed, and on the ground below.

Why am I here? In 1972, powerful Hurricane Agnes ravaged the East Coast of the U.S., doing $3.1 billion of damage and destroying part of the town I grew up in: Laurel, Maryland. It took years to repair all the damage from Agnes.

So, when I was invited by the world-famous Hurricane Hunters of the 53d Weather Reconnaissance Squad at Keesler AFB in Biloxi, Mississippi, I was in. My pilot, Lt. Col. Sean Cross, has penetrated hurricanes more than 165 times, so I felt relatively safe.

To be clear, this was not a joyride. During the flight, we would be gathering data important to predicting the strength and direction of the storm, including wind speed, barometric pressure, temperature, and humidity. Such information can potentially save billions of dollars in property damage, as well as countless lives.

The Hurricane Hunters have a long and storied history. Formed in 1943 as a barroom dare, the intrepid group has been active at Keesler since 1973, flying a myriad of weather reconnaissance missions. They are even more critical now, given cuts to NOAA and other government weather services by the current administration.

Like many hurricanes, Dorian started as a small tropical depression in the Caribbean Sea. As warm water and high humidity fueled its growth, the storm began to take on historic proportions. It is one of the most powerful hurricanes ever to have developed on the Atlantic Ocean side of the United States.

Coming into the Eye was no picnic. First, we had to travel three-and-a-half hours over the Gulf of Mexico and Florida to reach the storm. That part of the ride was fairly uneventful as we sat, belts fastened along the side of the fuselage, like you might see when military parachutists are waiting to jump. There was a toilet in the plane surrounded by a curtain. Occasionally, the crew would launch a radiosonde out of the back of the aircraft to measure atmospheric and water dynamics as it fell into the sea, some 10,000 feet below.

But as soon as we hit the Eye-wall, about five miles from the Eye, or hurricane’s center, the ride became very, very bumpy. For me, the gyrations made it difficult to take photos but wasn’t turbulent enough to make me sick. We each had a barf bag, of course, just in case.

In the end, we crisscrossed the monster storm several times collecting data, with four passes through the Eye. The last pass was the most violent, as the hurricane hit Category 5 status with winds over 185 mph.

The entire flight had taken 12 hours, 30 minutes: five hours in the storm itself, 30 minutes in the Eye, and seven hours traveling back and forth. The brave airmen on our flight do this kind of mission on a regular basis. Cross, for example, was going back out in a few days.

Where did Dorian land? It first devastated the Bahamas, as it pretty much stalled over them. The death toll six years later, including missing persons, is estimated to be at least 600, with property damage of $3.4 billion.

Luckily, Dorian stayed out in the Atlantic, not hitting the U.S. mainland directly but snaking up the coast into eastern Canada, still doing damage and eventually petering out. Cross says that the missions conducted by the Hurricane Hunters improve forecast accuracy by as much as 25 percent. Hopefully our flight contributed to that percentage. It’s at least one number to feel good about.

Jim Clash immerses himself in extreme adventures for Forbes magazine. He graduated from Laurel High School in 1973. His latest book is Amplified: Interviews With Icons of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Comments